Akbar, the third Mughal emperor, reigned from 1556 to 1605 and is celebrated as one of India’s greatest rulers. Ascending to the throne at a young age, he expanded the Mughal Empire and implemented transformative policies that fostered religious tolerance and cultural integration. This article aims to study in detail Akbar’s administrative reforms, military campaigns, policies on religious tolerance, and the cultural renaissance that flourished under his reign.

About Akbar

- Akbar, the third Mughal emperor, reigned from 1556 to 1605 and is often celebrated as one of the greatest rulers in Indian history.

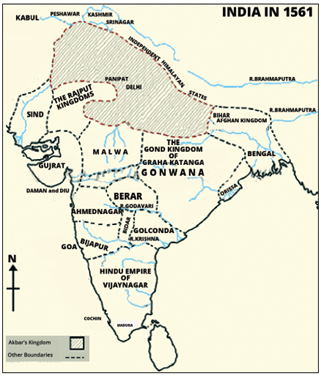

- Ascending to the throne at a young age, he rapidly expanded the Mughal Empire to encompass much of the Indian subcontinent.

- Renowned for his visionary policies, Akbar implemented administrative reforms promoting religious tolerance and cultural integration, establishing a legacy of pluralism and governance resonating throughout the empire.

- His commitment to fostering dialogue between different faiths and his patronage of the arts laid the foundation for a vibrant cultural renaissance.

Read our detailed article on the Mughal Empire, Babur, Humayun, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb, Mughal Administration, Mansabdari System, Jagirdari System and Decline of the Mughal Empire.

Contests during Akbar’s Reign

From 1561 to 1567, Akbar faced several significant rebellions, including:

- Maham Anga and Adham Khan: Maham Anga, Akbar’s foster mother, played a role in the dismissal of Bairam Khan.

- Her son, Adham Khan, claimed sovereignty after being sent on an expedition to Malwa.

- He killed the acting Wazir when removed from command, inciting Akbar’s wrath. In 1561, Akbar had him executed by throwing him from the fort parapet.

- Uzbeks: The Uzbek nobility greatly influenced eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Malwa.

- Initially assisting the Emperor in subduing Afghan forces, they grew arrogant and rebelled against Akbar’s authority.

- Akbar suppressed these revolts multiple times after 1561. In 1565, he declared Jaunpur his capital until he defeated them. He ultimately killed the Uzbek leader in 1567, effectively ending their rebellion.

- Mirzas: The Mirzas, Timurids related to Akbar through marriage, controlled western Uttar Pradesh and also revolted against him. Akbar defeated them, forcing their retreat to Malwa and Gujarat.

- Mirza Hakim: Akbar’s half-brother, who had taken control of Kabul and Lahore, was declared ruler by the Uzbeks. In 1581, Akbar marched to Lahore and compelled him to retreat.

Expansion of Empire (1560-76 AD)

Malwa

- The Kingdom of Malwa, with Mandu as its capital, was ruled by Baz Bahadur (1555-62). Baz Bahadur was a patron of art, and during his reign, Mandu became a celebrated centre for music.

- This period is associated with the romance of Baz Bahadur and Rani Roopmati, who was famous for her beauty, music, and poetry.

- However, the state’s defences were neglected, taking advantage of which Adham Khan led an expedition against Malwa and defeated Baz Bahadur, who escaped from Malwa (1561).

- However, Adham Khan made a mistake when he tried to abduct Roopmati, as she chose to embrace death rather than be part of his harem.

- The cruelty of Adham Khan led to a reaction against the Mughals, enabling Baz Bahadur to recover Malwa.

Garh-Katanga

- The Kingdom of Garh-Katanga included Narmada Valley and the northern parts of present-day Madhya Pradesh, with Chauragarh near Jabalpur as its capital. Aman Das consolidated it in the second half of the fifteenth century.

- He had helped Bahadur Shah of Gujarat conquer Raisen and was bestowed the title of Sangram Shah.

- His son was married to the Chandella Princess, Durgavati. She ruled as the Queen Regent when Asaf Khan, the Mughal Governor of Allahabad, invaded Garh-Katanga.

- Rani fought gallantly despite her allies’ betrayal but was wounded and feared imminent defeat. She stabbed herself to death to avoid capture.

- However, the Mughal Governor sent only a small proportion of the plunder to the royal court and kept the rest for himself.

- When Akbar learned about this, he forced Asaf Khan to part with his illegal gains and restored the Kingdom of Garh-Katanga to Chandra Shah, the younger son of Sangram Shah.

Rajputana

- After consolidating his dominance over Northern and Central India, Akbar turned his attention towards Rajputana, which presented a formidable threat to his supremacy.

- He had already established his rule over Ajmer and Nagaur. Beginning in 1561, Akbar started his quest to conquer Rajputana.

- He employed force and diplomatic tactics to make the Rajput rulers submit to him. Although many Rajput kingdoms accepted Akbar’s suzerainty, Udai Singh of Mewar and Chandrasen Rathore of Marwar refused to bow down.

- Rana Udai Singh was the descendant of Rana Sanga, who had died fighting Babur at the Battle of Khanwa in 1527.

- As the head of the Sisodia clan, he possessed the highest ritual status of all the Rajput kings and chieftains in India. Thus, it was of paramount importance for Akbar to defeat Mewar.

Gujarat

- Gujarat’s state was rich because of its fertile soil and prosperous foreign trade. Akbar also wanted to annex it because the Mirzas had taken shelter there and could be a potent threat to his Empire.

- Akbar wanted to prevent such a rich province from becoming a rival power centre.

- For these reasons, he advanced to Ahmedabad through Ajmer in 1572 and forced the Ahmedabad ruler to surrender without a fight.

- Following this, Akbar defeated the Mirzas ruling Broach, Baroda and Surat.

- In Cambay, Akbar saw the sea for the first time and met the Portuguese. The Portuguese were keen to establish an empire in India, but their designs were frustrated by Akbar’s conquest of Gujarat.

- However, when Akbar returned to Agra, rebellions were all over Gujarat. In 1573, Akbar again marched to Ahmedabad and defeated the enemy forces.

Bengal

- Afghan leader Daud Khan ruled the region of Bengal and Bihar. He maintained a powerful army of 40,000 cavalry and 1,50,000 infantry.

- Akbar marched steadily and captured Patna, thus securing Mughal communications in Bihar.

- After this, Akbar returned to Agra and took charge of a campaign for Munaim Khan, who invaded Bengal. Daud was forced to sue for peace, but soon afterwards, he raised the banner of rebellion.

- Mughal forces defeated him again, and Daud Khan was executed in 1576, thus ending the last Afghan kingdom in Northern India.

- The campaign of Bengal marked the end of the first phase of Akbar’s expansion of the empire. This also gave Akbar time to strengthen the administrative machinery of his empire.

Land Revenue Policy of Akbar

- Zabti: This land measurement system assessed revenue based on land productivity and local prices.

- It relieved peasants, allowing for remission in cases of low productivity due to droughts, floods, or disasters.

- This system is often associated with Raja Todar Mal, who had previously served as the revenue minister under Sher Shah.

- Dahsala System: An advanced modification of the Zabti system, the Dahsala system determined revenue based on the average produce of different crops and the average prices prevailing over the last ten years.

- Under this system, one-third of the average produce was allocated as the state’s share.

- Batai or Ghalla Bakshi: In this system, produce was divided in a fixed proportion between the state and the peasants.

- Peasants could pay either in cash or kind, with cash preferred. Although this system was fair, it required honest officials for effective implementation.

- Nasdaq: Also known as Kankut or estimation, this system involved a rough estimate of a peasant’s revenue based on past payments.

Major Revenue Assessment System introduced by Akbar

For revenue assessment introduced by Akbar, the land was classified based on continuity of cultivation:

- Polaj: The land which remained under cultivation almost every year.

- Parati: Fallow land, parati land paid at the full rate (polaj) when cultivated.

- Chachar: Land which had been fallow for 2-3 years.

- Banjar: Land which had been fallow for more than three years.

Mansabdari System

- Consolidating the Empire to such stretches was only possible with an organised nobility and a robust army unit.

- Akbar achieved both these objectives through the Mansabdari System. This was a system unique to the Mughal administration.

- Under this, every officer was assigned a rank (mansab), the lowest being ten and the highest being 5000 for nobles. Princes of the blood received higher mansabs.

- Remarkably, a noble’s highest rank was raised from 5000 to 7000 towards the end of Akbar’s rule.

- Two senior nobles of the Akbar rule, Mirza Aziz Koka and Raja Man Singh, were accorded the rank of 7000 each. The mansabs were divided into two:

- Zat: It was the personal rank, and the status and salary of the officer were fixed according to it.

- Sawar: This indicated the number of cavalrymen (sawars) a mansabdar was required to maintain.

- There were three categories within the mansab:

- The officer who maintained as many sawars as his zat rank.

- The officer who maintained half or more sawars than his zat rank.

- The officer who maintained less than half sawars than his zat rank.

- Every mansabdar had to bring his contingent for inspection regularly. Every sawar was identified based on his descriptive roll (chehra), while every horse was branded with imperial marks (dagh system).

- For every ten sawars, mansabdars had to maintain twenty horses. This was called the 10-20 rule.

- The salary to the mansabdars was paid by assigning them jagirs, which assigned the land revenue from an area to the mansabdar. This was not a hereditary system but rather only a mode of payment.

- Out of this salary, the mansabdar had to pay the soldiers and maintain a certain number of horses and elephants. Only the best-quality horses were retained in the army.

- The system was based on merit, and an officer who was generally appointed at lower mansab could rise in the hierarchy based on his performance. Similarly, an officer can be demoted in rank as a mark of punishment.

- Also, Akbar encouraged mixed contingents of all nobles- Mughal, Pathan Hindustani, Rajputs.

- This discouraged the forces of parochialism and tribalism. In addition to cavalrymen, bowmen, musketeers (bandukchi), sappers, and miners were also recruited from the contingents.

Read our detailed article on the Mansabdari System.

Political Administration during Akbar’s Reign

- The political administration during Akbar’s reign can be seen in various administrations such as:

- Central Administration,

- Provincial Administration,

- Local Administration and

- Revenue Administration.

All these political administration levels have been discussed in detail in the following section.

Central Administration

Akbar organised the central administration of the Mughal Empire based on the principles of separation of powers and checks and balances. Key functionaries in this system included:

- Wazir: As the head of the revenue department, the Wazir was responsible for overseeing all empire income and expenditures.

- While he served as a crucial link between the ruler and the administration, his role as the principal advisor remained strong, with many nobles holding higher mansabs than he did.

- Mir Bakshi: The head of the military department and considered the leader of the nobility, the Mir Bakshi recommended officers for various mansabs.

- However, the Wazir assigned jagirs to the mansabdars, maintaining a system of checks and balances.

- Additionally, the Mir Bakshi oversaw the empire’s intelligence and information agencies, managing several intelligence officers (braids) and news reporters (waqia-navis) stationed throughout the country.

- Mir Saman: Responsible for the imperial household, the Mir Saman ensured the provision of various items required by the inhabitants of the harem or female apartments, with many goods manufactured in royal workshops or karkhanas.

- Chief Qazi: This official headed the judicial department, overseeing legal matters and the administration of justice.

- Chief Sadr: The Chief Sadr managed charitable and religious endowments, ensuring proper administration and distribution.

Provincial Administration

- In 1580, the Mughal Empire was divided into twelve provinces, each led by a Governor (Subedaar).

- Other officials included a diwan, a Bakshi, a Sadr, a Qazi, and a waqia-navis, ensuring that the principles of checks and balances were upheld at the provincial level.

Local Administration

The provinces, or Subas, were further divided into Sarkars (equivalent to districts) subdivided into Parganas (similar to tehsils). The chief officers of a Sarkar included:

- Fauzdar: Responsible for maintaining law and order within the jurisdiction.

- Amalguzar: Tasked with assessing and collecting land revenue, the Amalguzar supervised land holdings to ensure uniform assessment and collection of revenues.

Revenue Distribution

For revenue management, the empire’s territories were categorised into three types:

- Jagir: Revenue was allocated to nobles and members of the royal family.

- Khalisa: Revenue that was sent directly to the royal exchequer.

- Inam: Revenue designated for religious figures, regardless of their faith. Most of this land consisted of cultivable wasteland, incentivising the Inam holders to promote agricultural extension.

Relations of Akbar with Rajputs

- At a time when the Mughal Empire was facing challenges from Afghans, internal rebellion, and foreign powers, Akbar desperately needed more allies and fewer enemies.

- He had realised that the Rajputs, who held large areas in their possession, were skilful warriors renowned for their valour and fidelity to their word and could safely be depended upon.

- Thus, he converted them into friends. Hence, Mughal Emperor Akbar sought the Rajputs’ cooperation to expand the Mughal Empire.

- In pursuance of this policy, he not only accorded high positions to the Rajput rulers who accepted his sovereignty but also entered into marriage alliances with them.

- Due to this liberal policy, Akbar found one of the most trusted allies in Raja Bharmal of Amber. He was made a high grandee, and Akbar married her daughter, Harkha Bai.

- While marriages between the Muslim Emperor and Hindu rulers were not unusual, Akbar elevated the relationship by giving his Hindu wives complete religious freedom.

- Bhar Mal’s son, Bhagwant Das, was accorded a mansab of 5000, while his grandson, Man Singh, rose to the rank of 7000, held by only one other noble, Aziz Khan Kuka.

- Akbar abolished the pilgrimage tax on Hindus in 1562 and Jizya in 1564 to show his equality towards the Hindu subjects.

- The autonomy given to the Rajput rulers made them realise that accepting the suzerainty of the Mughal Emperor did not harm their interests.

Religion during Akbar’s Reign

- Akbar was born when the Bhakti and Sufi movements were at their peak, and the idea emphasised essential unity of Hindus and Muslims was prevalent.

- Such liberal sentiments had a great impression on young Akbar, who abolished Jizya, the pilgrimage tax and the practice of forcibly converting prisoners of war to Islam.

- He followed the policy of Sulh-i-Kul, under which the ruler was distinguished by his paternal love towards his subjects without distinction of sect or creed.

- It was his duty to prevent sectarian strife from rising. He aimed to “ascertain the truth, to discover and disclose the principles of genuine religion.”

- In 1575, Akbar built Ibadat Khana, or the Hall of Prayer, in his new capital, Fatehpur Sikri. He invited theologians, mystics, and learned nobles to discuss religious matters there.

- The proceedings were at first confined to Muslims but were later opened to people of all religions, even atheists.

- He invited Purushottam and Devi to expound the doctrines of Hinduism, Maharji Rana to explain the principles of Zoroastrianism, Portuguese Acfquaviva and Monserrate for Christianity, and Hira Vijaya Suri for Jainism.

- However, the orthodox Mullahs did not like this, and rumours spread that Akbar wanted to forsake Islam.

- The growing strife forced Akbar to discontinue the discussions in Ibadat Khana in 1582. But he did not give up his quest for true religion.

Evaluation of Akbar’s Rule

- Akbar left a rich legacy for the Mughal Empire and the Indian subcontinent.

- He firmly entrenched the authority of the Mughal Empire in India and beyond after it had been threatened by the Afghans during his father’s reign, establishing its military and diplomatic superiority.

- His diplomatic policies were based on mutual coexistence and companionship, turning even the Hindu rulers into his allies.

- His ingenious political and military reforms gave the Empire long-needed stability.

- During his reign, the state became secular and liberal, emphasising cultural integration.

- He was a visionary, and his religious doctrine, Din-i-ilahi, with its secular orientation and faith in reason, held the promise of a modern India.

- It can also be stated that Akbar was born to rule, with a rightful claim to be among the greatest monarchs known to history.

Conclusion

Akbar’s reign left a lasting legacy, consolidating the Mughal Empire’s authority and establishing its military and diplomatic strength. His innovative reforms promoted stability and inclusivity, transforming traditional adversaries into allies. As a visionary leader, Akbar’s secular policies and quest for understanding among religions positioned him among history’s most remarkable monarchs.

Akbarnama

- Abu’l-Fazl wrote the Akbarnama, a detailed chronicle of the life and reign of the Mughal Emperor Akbar.

- The work, commissioned by Akbar himself, is divided into three volumes, covering his genealogy, administration, and personal philosophy.

- Abu’l-Fazl meticulously documented Akbar’s military campaigns, administrative reforms, religious policies, and interactions with various religious and cultural groups, presenting Akbar as a ruler committed to justice and harmony.

- The Akbarnama also includes vibrant miniatures that depict vital moments from Akbar’s life, making it an essential cultural artefact reflecting the grandeur of the Mughal court and Akbar’s vision for a unified, diverse empire.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How did Akbar die?

Akbar died after a prolonged illness, possibly due to dysentery.

Who was the father of Akbar?

Akbar’s father was Emperor Humayun.

Who was the Son of Akbar?

Akbar’s son was Jahangir (also known as Prince Salim).