Aurangzeb was the sixth Mughal emperor, ruling from 1658 to 1707. He was known for his military conquests and strict religious policies. His reign is significant for its impact on the stability of the Mughal Empire, leading to internal strife and eventual decline. This article aims to study in detail the complexities of Aurangzeb’s reign, exploring his military strategies, administrative policies, religious intolerance, and the resulting social upheavals.

About Aurangzeb

- Aurangzeb ascended to the throne in AD 1658 and assumed the Alamgir title, “the Conqueror of the world”.

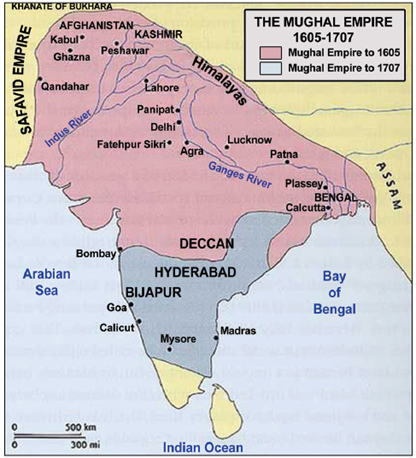

- He reigned for a remarkably long period of 50 years. From 1658 AD to 1681 AD, he remained in the north, but after this, the political scene shifted from the north to the Deccan.

- He was a great military commander and could crush the kingdoms of Bijapur and Golconda, but his struggle with the Marathas remained indecisive.

- Aurangzeb’s last twenty-five years of reign, which he spent in the Deccan, were disastrous for the empire, as bankruptcy and maladministration threatened to break it apart.

- Muhammad Akbar, the rebellious son, revolted against his father Aurangzeb in 1681, weakening Aurangzeb’s position against Rajputs.

- Aurangzeb had the highest number of Hindu generals in the Mughal army.

- Aurangzeb constructed ‘Bibi ka Maqbara’, an architectural wonder with intricate design, carved motifs, imposing structures, and a beautifully landscaped Mughal-style garden. It is also known as Rabia-ud-Durani or the Second Taj Mahal.

- Aurangzeb built the Moti Masjid inside the Red Fort in Delhi.

- The Mansabdari system was introduced mainly to effect clean administration.

- The Portuguese introduced tobacco to India in 1605. The Mughal emperor Jahangir noticed its harmful effects and ordered to ban it in 1617 AD.

Read our detailed article on the Mughal Empire, Humayun, Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, Mughal Administration, Mansabdari System, Jagirdari System and Decline of the Mughal Empire.

Popular Revolts by Aurangzeb

In the first phase, Aurangzeb had to deal with revolts for local independence, including those of Jats, Satnamis, Sikhs, and Bundelas.

Jats

- The Jats in the region of Delhi and Mathura were the first to revolt. The Jats revolt had a peasant–rural background, and they used the area’s rugged terrain to their advantage.

- In 1669 AD, they raised the banner of rebellion under the leadership of a local Zamindar, Gokula.

- However, they were defeated as Aurangzeb personally marched against them.

- But the Jats continued their resistance, and in 1685, there was a second uprising under Rajaram’s leadership.

- Jats were much better organised this time and offered a tough fight to Raja Bishan Singh, the Kachhawah ruler appointed by Aurangzeb to crush the rebellion.

- However, the rebellion ended in 1691, and Rajaram and his successor, Charuman, were forced to submit.

- Later, in the eighteenth century, taking advantage of the weakening authority of the Mughals, the Jats under Charuman established an independent principality for themselves.

Satnamis

- The Satnamis were a peace-loving religious sect mainly consisting of peasants, artisans and low-caste people.

- They did not observe distinctions of caste and rank between Hindus and Muslims.

- The revolt began in 1672 AD due to their conflict with a local officer and soon grew in extent.

- However, the Satnamis were defeated as Aurangzeb marched in person to Narnaul, a place near Mathura, to crush the revolt.

Bundelas

- The Bundelas, a Rajput clan of Bundelkhand, revolted against Aurangzeb’s religious policies, which were perceived to be discriminatory against Hindu subjects.

- However, the Mughal army successfully suppressed the revolt.

Sikhs

- The Sikh community emerged when the Guru Nanak founded the new religious sect.

- Earlier, the relations between the Sikhs and Mughals were harmonious as the fourth Guru, Ram Das, was revered by Akbar and was presented with a land grant in Amritsar.

Rajput Policy of Aurangzeb

- Aurangzeb failed to realise the value of an alliance with the Rajputs, which had contributed so much to the growth of the Mughal Empire since Akbar’s time.

- Aurangzeb’s relationship with the Rajputs began to deteriorate after the death of Raja Jai Singh of Ambar and Raja Jaswant Singh of Marwar.

Deccan Policy of Aurangzeb

- Aurangzeb had already been Deccan’s viceroy during Shah Jahan’s reign. He wanted to follow an aggressive Deccan policy but needed help in the first half of his reign as he was kept busy by the rebellions in the North and trouble with the Rajputs.

- Therefore, initially, the responsibility of looking after the affairs of the Deccan was left to Raja Jai Singh, who attacked Bijapur in AD 1665 but failed to get the submission of Adil Shah II.

- However, soon after Adil Shah II’s death, the state of Bijapur went into political turmoil due to infighting among the nobles.

- Taking advantage of this, Mughal commander Diler Khan attacked Bijapur in AD 1679, but still in vain.

- The Mughals were mainly unsuccessful because of the tripartite alliance of Bijapur, Golconda, and Marathas under Shivaji.

- The three forces stood united against the Mughal attack despite conflicts.

- Thus, the Mughals failed to succeed until Aurangzeb reached Deccan in 1681 AD.

Religious Policy of Aurangzeb

- Aurangzeb was a zealous Sunni Muslim. He tried to enforce Quranic laws strictly. Muhtasibs were officials appointed in all provinces to check that people lived their lives according to Sharia.

- He discontinued the practice of Jharokha-Darshan, as he considered it a superstitious practice against Islam. He forbade music in the court even though he was a proficient veena player.

- Initially, he forbade the destruction of old Hindu Temples and only banned the construction of new ones. But after the revolt of Jats, Satnamis, and Rajputs, he changed his policy and consented to the destruction of even old Hindu Temples.

- The celebrated temples at Mathura and Banaras were reduced to ruins. In 1679 AD, he revived the Jizya tax on non-muslims.

- This led to widespread resentment among the Hindu subjects as they considered Jizya to be discriminatory against them.

- Aurangzeb was also not tolerant of other Muslim sects. His invasions against the Deccan sultanates were partly due to his hatred of the Shia faith, as the Deccanis were Shias.

- He was also against the Sikhs, and he executed the ninth Sikh Guru Tej Bahadur. This had resulted in the transformation of Sikhs into a warring community, Khalsa.

- Although Aurangzeb’s religious policy had political motives behind it, he reversed the policy of religious tolerance that his predecessors followed.

- The religious orthodoxy practised by Aurangzeb led to several revolts by the Marathas, Satnamis, Sikhs and Jats.

- These revolts destroyed the empire’s peace, disrupted its economy, and weakened its military strength, ultimately leading to Aurangzeb’s failure and the downfall of the Mughal Dynasty.

Administration during Aurangzeb’s Reign

- The administration under Aurangzeb was highly centralised. He looked into the minute details of administration, read the petitions submitted to him, and either wrote or dictated orders. All his officers and ministers of Administration were kept under his strict control.

- The ministers of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb were reduced to mere clerks, as the Emperor himself made all the critical decisions.

- This resulted in great administrative degeneration and helplessness.

- Thus, though the administration’s framework remained the same as under his predecessors, the manner and spirit of implementation changed vastly.

- At the time of Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, the Mughal Empire consisted of twenty-one provinces, fourteen of which were situated in Northern India; one was Afghanistan, and the remaining six were in the Deccan.

- As in Akbar’s time, every province had a Governor, a diwan, and other officers to assist in governance.

- During his reign, the provincial administration considerably deteriorated because of his more than twenty-five years’ absence from Northern India and continuous wars in the Deccan.

- Local chiefs and zamindars in several provinces disregarded law and order as a natural result of the central authority’s weakening caused by the emperor’s obsession with never-ending wars and his unwise policy of religious intolerance.

- Besides the land revenue, other important government income sources were zakat (realised from Muslims), jizya (poll tax from Hindus), salt tax, customs duty, mint and spoils from war.

- The mode of assessment and collection of revenue established by Akbar was replaced by the revenue farming system, which allowed the contractors to realise the revenue from the peasants directly, not by the state officials under the direct supervision of the government.

- Because of this change, the condition of the peasants was worse than under Akbar or Jahangir.

- Foreign trade did not play an important role in the Mughal Empire’s economy. India exported indigo and cotton goods. After agriculture, the cotton industry employed the most people.

- The chief imports into the country were glassware, copper, lead and woollen cloth.

- Horses from Persia, spices from the Dutch Indies, glassware, wine, curiosities from Europe, slaves from Abyssinia, and superior kinds of tobacco from America were also imported.

- However, the trade volume was small, and the government’s income from import duties was not more than 30 lakhs of rupees a year.

- The Mughal army under Aurangzeb had increased considerably. He was engaged in fighting throughout his life, and naturally, he needed a much larger army than his predecessors.

- The expenditure on the army under Aurangzeb was roughly double that under Shah Jahan.

- However, despite the emperor’s vigilance and strictness and his ability as a general, the Mughal army’s administration system and discipline were far inferior to those of Akbar.

Evaluation of Aurangzeb’s Reign

- Aurangzeb died in 1707 AD, leaving a vast empire on the verge of bankruptcy and collapse.

- His rigid religious policies alienated not only the Hindus and Sikhs but also the liberal-minded Muslims, and he lost the loyalty of most of his subjects.

- His Deccan campaigns had drained the treasury and disrupted trade and commerce.

- His preoccupation with the Deccan and the extended stay there led to many revolts in the north, as the nobles, the Sikhs and the Rajputs tried to assert their independence.

- Moreover, being suspicious of his sons, he kept them as far away from himself as possible.

- Consequently, they failed to receive proper administrative training and became pleasure-loving.

- The administration had become over-centralised, and when Aurangzeb’s iron hand became still after his death, chaos ensued, and the empire disintegrated quickly.

Conclusion

Aurangzeb’s death in 1707 left the Mughal Empire on the brink of collapse. His centralisation efforts and rigid policies alienated key sections of society, contributing to internal revolts and economic strains from his Deccan campaigns. As his control weakened, chaos ensued, leading to the rapid decline of the empire. His reign serves as a critical reminder of the importance of tolerance and the dangers of excessive centralisation in governance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How did Aurangzeb die?

Aurangzeb died due to natural causes, primarily complications from illness, after suffering from poor health for several years. He passed away while on a military campaign in the Deccan region.

When did Aurangzeb rule India?

Aurangzeb ruled India from 1658 until he died in 1707, encompassing a reign of nearly 50 years.

Who was Aurangzeb’s father?

Aurangzeb’s father was Shah Jahan, the fifth emperor of the Mughal Empire, renowned for his architectural achievements, including the Taj Mahal.

Who was Aurangzeb’s son?

Aurangzeb’s son was Bahadur Shah I, who succeeded him as the emperor of the Mughal Empire. Bahadur Shah I ruled from 1707 to 1712 and faced significant challenges maintaining the empire’s unity and authority.