The Gupta Economy was primarily agrarian, with agriculture being the mainstay, while trade, crafts, and industries also played a significant role in its prosperity. The flourishing economy led to the rise of a strong guild system, advancements in trade, and the issuance of gold coins, symbolising the wealth and stability of the empire. This article aims to study the Gupta economy in detail, including agriculture, trade, the guild system, currency, factors that contributed to its eventual decline, and other related aspects.

About Gupta Empire

- The Gupta Empire was an ancient Indian empire founded by Sri Gupta.

- The Gupta Empire stretched across northern, central and southern parts of India between 320 and 550 CE.

- The period is called the Golden Age of India due to its achievements in the fields of arts, architecture, sciences, religion, and philosophy.

- During this era, India witnessed a renaissance in cultural and intellectual pursuits, with significant contributions from figures like Kalidasa in literature and Aryabhata in science.

- The Gupta rulers fostered an environment of stability and prosperity, facilitating advancements in various fields and leaving a lasting legacy on Indian civilisation.

Read our detailed article on the Gupta Empire, Gupta Administration, Gupta Society, Gupta Science and Technology, Gupta Literature, Gupta Art and Architecture, Guild System and Gupta Inscriptions.

Gupta Economy

- During the Gupta period, the Gupta economy was characterised by flourishing trade, a well-functioning guild system, flourishing manufacturing industries, and a high standard of living.

- Of course, agriculture was the main occupation of the people. Still, other occupations, like commerce and the production of crafts, had become specialised occupations in which different social groups were engaged in the Gupta economy.

Agriculture during Gupta Period

The agricultural period during the Gupta Empire can be seen as follows:

- Crops: All the major categories of crops—cereals like barley, wheat, and paddy, different varieties of pulses, grains, and vegetables, and cash crops like cotton and sugarcane—continued to be cultivated.

- Irrigation: A generous nature and establishment of irrigation works helped expand agriculture. Lakes and reservoirs were used for irrigation. Another irrigation method was to draw water from wells and supply the water to the fields through carefully prepared channels.

- Condition of Cultivators: The condition of ordinary cultivators may be considered to have been rather nasty due to the following reasons;

- Some historians believe that the practice of land grants reduced the peasant population as a whole to a shallow position in society.

- In many areas, the appearance of small kingdoms of new rulers and their officials and sections of people who did not participate in agriculture created great inequalities in society. It imposed a great burden on actual tillers of the soil.

- The state’s taxes on producers also increased during this period. Further, the practice of imposing vishti, or unpaid labour, was also in vogue.

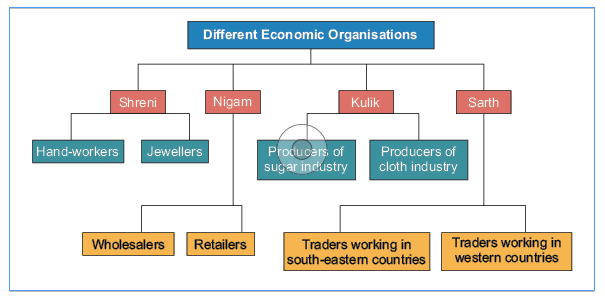

Guild System during Gupta Period

- A guild is an association of artisans or merchants who oversee the practice of their craft in a particular area.

- In the Gupta Era, the activities of Guilds increased considerably. Guilds came to acquire considerable autonomous power.

- These trade guilds were both politically and economically influential. Guilds could control one trade in a province and wield economic dominance.

- Moreover, they became politically influential and also started maintaining militias.

- They facilitated the functioning of both craftsmen and traders.

- Guilds continued to be the nodal points of commercial activity. They were almost autonomous in their internal organisation.

- The government respected their laws. A corporation made the laws governing the guilds of guilds, each of which had a member.

- The corporation elected a body of advisers who functioned as its functionaries. Some industrial guilds, like the silk weavers, had separate corporations.

Read our detailed article on the Guild System.

Economic Regulations during Gupta Period

- The Gupta government established various laws and regulations to ensure a smooth trade flow, which influenced the Guptas’ economic life.

- The Smritis, or law books, laid down the principle that it was the royal duty to encourage trade and the arts.

- The Guptas also laid down various regulations on trade. It was said that imported commodities should be taxed at the rate of 1/5th of the value as a toll.

Currency during Gupta Period

- Numismatic evidence is an essential source of information about Gupta’s history. The vast number and variety of gold coins indicate the empire’s economic prosperity.

- The coins of Gupta Period also highlight the time’s political, cultural, and religious history. The metrical legends on the coins indicate the rulers’ high literary taste and valour.

- The Asmavedha-type coins of Samudragupta and Kumaragupta I reveal the performance of horse sacrifices.

- The coins of Gupta Period provide new facts and corroborate the information obtained from epigraphic and literary sources.

- It is not easy to ascertain who introduced the Gupta currency system.

- Until recently, it was held that Chandragupta I was the originator of the currency system and that the Chandragupta-Kumaradevi type of gold coins were the earliest gold coins of the dynasty.

- However, some scholars have suggested that Samudragupta first issued Gupta coins, that his first gold coins were of the standard type, and that later, he issued the Chandragupta-Kumaradevi type of coins to commemorate his father’s marriage to the Lichchhavi princess.

- The minting of silver coins first started during Chandragupta II’s reign and was continued by Kumaragupta I and Skandagupta.

- Along with gold and silver coins, copper coins were also issued, though to a much-limited extent.

- Copper coins have been scarce from the Gupta period onwards.

- The Gupta rulers did not issue as many copper coins as their predecessors.

- The Indo-Greeks, especially the Kushanas, issued many copper coins, which were evidently in common use in different parts of their territories.

- The comparative scarcity of the coins of Gupta Period shows that there was hardly any accessible medium through which people of one town could exchange relations with those of the other.

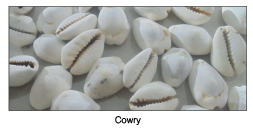

- The gold coins of the Gupta Period issued by the Gupta rulers could be helpful only for significant transactions like the sale and purchase of land. Smaller transactions were conducted through the barter system or cowries.

- Therefore, it is argued that the Indian economy in the Gupta period was largely based on self-sufficient production units in villages and towns and that the money economy was gradually weakening.

Coins of Gupta Period

- The coins of Gupta Period (4th-6th centuries AD) followed the tradition of the Kushans, depicting the king on the obverse and a deity on the reverse; the deities were Indian, and the legends were in Brahmi.

- The earliest coins of Gupta period are attributed to Samudragupta, Chandragupta II and Kumaragupta.

- The coins of Gupta Period often commemorate dynastic succession as well as significant socio-political events, like marriage alliances, the horse sacrifice, etc. (King and queen type of coin of Chandragupta-I, Asvamedha type, etc.), or, for that matter, the artistic and personal accomplishments of royal members (Lyrist, Archer, Lion-slayer, etc.).

- Historians have tried to put forward this theory of paucity of coins from 500-1000 CE.

- According to them, the period between 300 CE to 500 CE witnessed many coins, especially the gold ones issued in the Gupta period (Photos of coins of the Gupta period are given above).

- The number and purity of gold coins declined sharply thereafter. From the Gupta period onwards, the rise of independent and self-sufficient local units witnessed the paucity of coins of common use.

Reasons for Shortage of Gold Coins (650-1000 CE)

Some historians have evaluated the causes and assigned two factors for the shortage of the coins of Gupta Period:

- Northern India formed a wider exchange zone with Central Asia during the earlier two centuries.

- In this phase, the Indian traders operated as intermediaries or direct traders with Byzantium.

- However, around 650 CE, the Byzantine people learned to grow the art of silk, which lessened their dependence on Indian traders.

- The Gupta economy saw a decline in the silk trade, hampered the gold inflow from Central Asia to India.

- The decline of Roman gold and silver began after the third century CE. The Romans were unaware of the drain on their coins, which were exported to India as part of the general trade in metals.

- Moreover, there are references to the drastic reduction of Roman precious metal coins flow to India after the 3rd century CE. The early medieval period also noticed a decay of classical cities in the Eastern Roman Empire and a decline of urban life in Byzantine.

- These led to little scope for trade between the Indian subcontinent and the Byzantine.

Post Gupta Coinage

- Post Gupta coinage (6th-12th centuries AD) is represented by a monotonous and aesthetically less interesting series of dynastic issues, including those of Harsha (7th century AD), Kalachuri of Tripuri (11th century AD), and early medieval Rajputs (9th-12th centuries AD).

- Gold coins struck during this period are rare. Gangeyadeva, the Kalachuri ruler who issued the ‘Seated Lakshmi Coins’, revived them, which later rulers copied in gold and debase form.

- The Bull & Horseman type of coins were the most common motif on coins struck by the Rajput clans.

- In western India, imported coins like the Byzantine solidi were often used, reflecting trade with the Eastern Roman Empire.

Exceptions to the Theory of Paucity of Coins

- Historians, however, have pointed out two exceptions to the theory of a paucity of coins in early medieval India.

- They agreed that there is evidence of the Shahi rulers of the Punjab and Afghanistan’s regular issuance of coins between 650 and 1000 CE.

- The rulers of Kashmir, too, issued a series of coins from the 6th to the end of the 10th century CE.

- Thus, apart from the Indo-Sassanian, Pratihara, and Eastern Chalukya coins, other dynastic coins were limited in quality and quantity between India’s seventh and tenth centuries.

- However, these coins had less intrinsic value than earlier ones. Whatever coins were found were of extremely poor quality, and their purchasing power reflected the decline of their actual role.

- Moreover, compared to the rising population and expanding settlement area, the total volume of money in circulation was quite less.

- During the post tenth century, many Rajput dynasties issued coins, in addition to the kings of Kashmir and Shahi rulers of Kabul.

- The Cholas and the Pandyas in south India and Eastern and Western Chalukyas in the Deccan-issued currency after the 10th century CE.

- Many debased coins of various metals were issued during this phase, which refers to the revival of trade and urbanism in the 11th century CE.

- Thus, many dynastic coins were found in both north and south India between 1000 and 1300 CE. Many pieces of evidence prove the existence of India’s trade with China and Egypt from the 11th century CE onwards.

Trade and Commerce

- The age of the Guptas was conducive to developing internal and external trade and commerce in the Gupta economy.

- After the decline of the Roman Empire, the Indo-Roman mercantile relations almost ended.

- There was increased trade with the other lands, particularly Southeast Asian countries.

- The arts and crafts and internal trades prospered considerably during this period.

- Industry and trade were generally prosperous, and the foreign trade balance favoured India.

- However, the most noteworthy change in foreign trade was the decline of the Roman trade and the decline of three important southern ports:

- Muziris,

- Arikamedu, and

- Kaveripattinam.

Nature of Trade during Gupta Period

- During this period, internal trade expanded to numerous trade centres in the Gupta economy. Kalidasa gives a very good description of the town market and its business transactions. We reference two types of merchants in the Gupta period, namely Sresthi and Sarthavaha. The former also acted as bankers or moneylenders. The sarthavahu, or caravan trader, was an important figure in city life.

- Goods: The articles of internal trade included all sorts of commodities for everyday use, chiefly sold in village or town markets.

- On the other hand, luxury goods formed the principal articles of long-distance trade.

- Regulation: Narada and Brihaspati have passed numerous laws and regulations to safeguard the interests of buyers and sellers alike, but dishonest practices were prevalent in the market.

- Prices/Weights: Prices in the Gupta period were not always stable and varied from place to place.

- Similarly, weights and measures were also different in different places.

- Mode of Transport: Internal trade was carried on by roads and rivers, and foreign trade was carried on by sea and land.

- We have numerous references to sea trade in the period, but the sea routes were not safe for merchants.

- We learn from Fa-hien that the Central Asian route from China to India was full of perils.

- Foreign Trade: Indian ports maintained regular maritime relations with Sri Lanka, Persia, Arabia, Ethiopia, the Byzantine Empire, China, and the islands of the Indian Ocean.

- Sri Lanka played an important role in both the foreign trade of the island and in the inter-oceanic commerce between the East and the West.

- China: India’s commercial relations with China flourished, and trade was conducted through land and sea routes.

- The volume of external trade between India and China greatly increased during the Gupta period.

- Chinese silk had a good market in India. Indo-Chinese maritime trade affected the fortunes of both countries.

- Byzantine Emperors: India’s trade with the West somewhat declined due to the decline of the Roman Empire, but revived again under the Byzantine emperors.

- The two most important items of export from India to the Byzantine Empire were Silk and Spices.

- The silk trade was so important that a law was enacted regulating silk prices all over the Byzantine Empire:

- Sri Lanka: Sri Lanka links the ports on India’s east and west coasts.

- Agricultural products, such as aloes, clovewood, and sandalwood, were sent from the east coast of India to Sri Lanka and thence exported to the Western and even Persian and Ethiopian ports.

- Trade relations with Western Asia flourished during the Gupta period, too.

Decline of Trade during Gupta Period

- Till A.D. 550, India carried on some trade with the Eastern Roman Empire, to which it exported silk.

- Around A.D. 550, the people of the Eastern Roman Empire learnt from the Chinese the art of growing silk, which adversely affected India’s export trade.

- Even before the middle of the sixth century A.D., the demand for Indian silk abroad had reduced.

- In the middle of the fifth century, a guild of silk weavers left their home in western India and migrated to Mandsaur, where they gave up their original occupation and took up other professions.

- The decline of trade was not limited to foreign trade. Long-distance internal trade, too, suffered owing to the weakening of links between coastal towns and interior towns and further between towns and villages.

- The decay of towns, shrinkage in urban commodity production, and the decline of trade were related problems.

- The decline of traders’ and merchants’ status in society during this period also indicates the falling fortunes of trade and commerce.

- The rise of numerous self-sufficient units dominated by landed beneficiaries also had an adverse effect on trade.

- Some sources suggest that traders moved through forests to avoid the multiple payment of duties.

- Sea voyages and long-distance travel were taboo. Such attitudes surely did not promote the cause of trade.

- However, this does not deny that trade in necessities such as salt, iron artefacts, etc., continued.

- Moreover, some long-distance trade went on unhindered, such as the trade of expensive luxury goods such as precious stones, ivory, and horses. The aristocracy, chiefs, and kings demanded such commodities.

Effect of Decline of Trade during Gupta Period

- The decline of trade and urbanisation, led to many social changes, such as the mode of agricultural production, the emergence of forced labour or Vishti, and the rise of the Brahmans as landholders and beneficiaries and servile peasantry.

- The Gupta tradition of coinage continued to decline in northern, central, and eastern India, as well as in eastern and western Deccan, until 650 CE.

- During this period, the dynastic coins also suffered a drastic reduction, as was evident in the kingdoms of the Palas, the Rashtrakutas, and the Gurjara-Pratiharas.

- Peninsular India also noticed a decline in the issuance of coins after the fall of the Satavahanas during the first half of the 3rd century CE and after the 6th century approximately for the next 400 years of the south Indian dynasties [especially Pallavas, Pandyas, Badami Chalukyas and Cholas] seemed to have discarded the practice of issuing coins.

- During the 500-1000 CE phase, the archaeological evidence of actual mints, moulds and dies is absent.

- Consequently, cowries served as the medium of exchange from the early medieval period until the British arrived.

- The use of cowries reflected the backward economy, where the decline of local and long-distance trade was evident.

- During the decline phase, the number of coins in the early medieval period increased in northern India, as did the population and area under settlement.

- Whatever coins were available were very rough and of less density than those in the proceeding phase.

- The shortage of money restricted the collection of cash revenue from peasants.

- Moreover, due to the absence of cash, military, administrative, and religious services were paid for through land grants.

Conclusion

The Gupta economy was a vibrant mix of agriculture, trade, and manufacturing, supported by a well-structured guild system and a thriving internal and external trade network. Despite the increasing burdens on the peasantry and the eventual decline of long-distance trade, the Gupta economy saw significant economic prosperity, reflected in the flourishing industries, the extensive use of gold coins, and the active participation of guilds in economic life. This economic transformation significantly influenced the socio-political landscape of post Gupta India.